Oaks of San Diego County I

Fred M. Roberts, CNPS-SD Rare Plant Botanist

Part 1: Oaks Red and Gold

Oaks appear to be one of the more popular native plants in California. There seem to be plenty of San Diego CNPS members that think so just based on the number of oak t-shirts I sold at the CNPS Chapter Plant Festival last fall and the number of people who have recently asked how the second edition of my oak book is coming along.

Oaks are indeed an interesting group and the identification of most species we find in San Diego County is pretty straight forward, even if at first glance they do not appear to be. One complex is not. The line between Engelmann’s oak (Quercus engelmannii), California scrub oak (Q. berberidifolia), and Muller’s oak (Q. cornelius- mulleri) is a bit blurry, as is the relationship of the name Torrey’s scrub oak (Q. X acutidens) to all three of them. I thought it high time that I write something about the oaks of San Diego County. There is enough to say that I decided to present this in three parts. Originally, I was going to try to do this in two but realized even then I might just fill an entire newsletter. So, three it is.

This first part sets the stage and focuses on our most straight forward species. The second part will delve into a bit of the history of oaks of San Diego County, which seems like it might help readers understand the relationship of the three oaks I called out by name earlier in this paragraph. The third part will be about the relationship of our most challenging white oaks (the four named above).

As a simple refresher, our oaks come in three main flavors, or sections as they are formally called: the red (or black oaks; it seems the “red oaks,” a name more widely used back East, has become the more widely used name), the intermediate or golden oaks, and the white oaks. If you can tell which section an oak is from, it goes a long way toward simplifying your identification task.

The red oaks are characterized by scaly acorn cups, leaves that have a bristle at the apex of teeth (if the leaves have teeth), and being densely hairy or silky on the inner surface of the acorn. With the exception of coast live oak (Quercus agrifolia), our red oaks require two years for the acorns to mature.

The golden oaks have thickened acorn scales that are mostly tuberculate (warty) and embedded with silky hairs, the leaves lack a bristle at their tip, and the inner lining of the acorn is glabrous (without hairs). The upper surface of the leaf is glabrous but the lower leaf surface is sometimes covered with waxy hairs. If it is, the hairs are golden hued or silvery. The acorns mature in two years.

The white oaks have tuberculate acorns that mature in one year. The leaves are typically toothed but lack spiny bristles at the tips of the teeth. In San Diego County our species are mostly evergreen though a couple semi- deciduous. All white oak leaves have minute trichomes, though these are sometimes deciduous and may only occur on the underside of the leaf.

It is important to remember when identifying virtually any oak, the leaves may not be at all characteristic of the species if the shrub or tree is resprouting after a fire or the branches have otherwise been cut. The leaves can then be very weird or unusual. Immature oak leaves can be hairy even in species that generally are without hairs when the leaves mature. For white oaks especially, minute star-shaped hairs, known as trichomes, can make or break an ID or lead even experts to complete bewilderment. Hybrids are common in oaks, but they do not cross section lines. Red oaks cross with red oaks. White oaks cross with white oaks. Golden oaks cross with golden oaks. There are no red oak/white oak crosses.

Within those restrictions, oaks can be promiscuous. They do not fit the old Darwinian concept that when species cross, their offspring will be sterile. In oaks, the hybrids are often quite fertile and backcrossing like crazy. I guess you could still make it work if you only wanted to recognize three wildly variable species of oak in North America but that would be a poor reflection of the diversity and genetic richness of these species.

Today, we recognize at least 10 species, two varieties, and three named hybrids in addition to several un-named hybrids in San Diego County. This is more oak taxa than any other one county in California. It makes San Diego County the best place to host an oak class in California and the easiest place to run an oak field trip. The list is long enough though, that it can also make San Diego County one of the more challenging places in California to put a name on an oak specimen. A list of the species and named hybrids goes like this:

Red Oaks

Quercus agrifolia var. agrifolia – Coast live oak

Q. agrifolia var. oxydenia – Southern coast live oak

Q. kelloggii – California black oak

Q. wislizenii var. frutescens – Scrub live oak

Q. wislizenii var. wislizenii – Scrub live oak

Q. X ganderi – Gander’s oak (Q. agrifolia var. oxydenia x Q. kelloggii)

Q. X morehus – Oracle oak (Q. kelloggii x Q. wislizenii)

Golden Oaks

Q. cedrosensis – Cedros Island oak

Q. chrysolepis – Canyon live oak

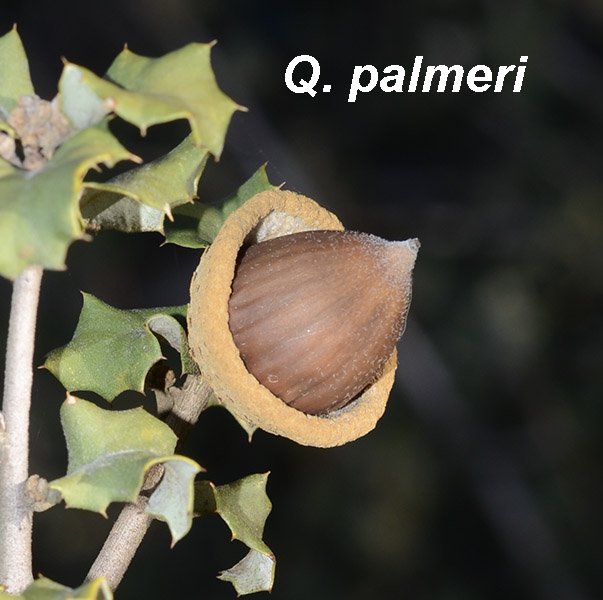

Q. palmeri – Palmer’s oak

White Oaks

Q. berberidifolia – California scrub oak

Q. cornelius-mulleri – Muller’s oak

Q. dumosa – Nuttall’s scrub oak

Q. engelmannii – Engelman’s oak

Q. X acutidens – Torrey’s oak (Q. engelmannii x Q. cornelius-mulleri)

The red oaks and golden oaks of San Diego County are not especially numerous or problematic.

Red Oaks

For the red oaks, there are three species. Coast live oak, already mentioned, is our most widespread species and is a familiar part of coast live oak woodlands and gallery forests across the county from the coast to the top of the mountains. There are two varieties, Q. agrifolia var. agrifolia and Q. agrifolia var. oxydenia (sometimes referred to as southern coast live oak or peninsular coast live oak).

Coast live oak is an evergreen tree with a rounded crown and distinctive convex (bubble-shaped) leaves with bristle-tipped teeth, and a dense patch of hair in the vein axils along the midvein. The acorns are long and spindle shaped, often striated (striped), and have a distinctly scaled acorn cup. The common form, found far into the northern California Coast Ranges, is otherwise glabrous (without hairs) on the lower side of the leaf. Southern coast live oak, which has been found as far north as the foothills of the San Gabriel and San Bernardino Mountains but is most characteristic of the foothills and mountains of central and southern San Diego County, has dense, white tomentose (woolly) hairs on the underside of its leaves.

In the higher mountains, the Laguna, Cuyamaca, and Palomar Mountains, we find California black oak (Q. kelloggii), a tree with deeply lobed leaves, each lobe with a long bristle tip. The leaves of California black oak are deciduous, emerging in the spring and falling off in the winter. California black oaks add a delightful splash of color to our mountain forest as their leaves turn yellow. The yellow gradually transfers to carpet the ground below the trees as the yellow leaves drift down, leaving the branches bare. The acorn is large, somewhat barrel-shaped and with scaled acorn cups.

Mixed in with the California black oaks and in the chaparral belt a band lower, there is scrub live oak, ours mostly shrubs (Q. w. var. frutescens) with relatively flat, planer leaves, and widely spaced spine-tipped teeth. The acorn on this scrub live oak is only of moderate size with scaled cups. The mature leaves of scrub live oak are glabrous (without hairs). In central California, the tree form (Q. w. var. wislizenii) is quite abundant. These typically have larger leaves and acorns, and sometimes stalked acorn cups. The tree form is uncommon in the mountains of San Diego County. The two forms of scrub live oak seemingly blend together and it may be that the difference is more ecological than truly genetic. Shrubs that haven’t burned in a very long time and have adequate moisture may eventually become trees. Those that burn more frequently or live on dry slopes may just stay shrubs. Farther north, where there is more moisture, trees are far more common. A similar situation occurs in canyon live oak but the two forms are not recognized as distinct taxa.

Here is some oak trivia for you. While I was aware that coast live oak had acorns that mature in a single season, I was not aware that was special until circa 1998 when a book customer from Israel wrote me a letter. He was aware of only one species of Mediterranean red oak that had fruit that matured in a single season and was intrigued that coast live oak also developed fruit annually. Indeed, coast live oak is one of only five species of red oak that share this character out of 35 species in Canada and the United States.

All three of our red oaks hybridize. However, hybrids are typically spotty and uncommon and occur where both parents come into contact (or once did). The hybrids of red oaks clearly show characteristics of both parents. Gander’s oak in San Diego County is a hybrid of Q. agrifolia var. oxydenia and Q. kelloggii, and has evergreen leaves, fairly shallow, bristle-tipped lobes, the acorns of California black oak, and the white tomentose underside of the leaf of southern coast live oak. There is a really nice one along SR-79 several miles north of Santa Ysabel.

Oracle oak (Q. X morehus) is a hybrid of Q. kelloggii and Q. wislizenii. Mostly it is between the shrub form here, and the resulting hybrid is a shrub or arborescent, leaves are green and glabrous (without hairs) with moderate lobes, and acorns similar to those seen on California black oak. There is a tree form of the Oracle oak, but it is scarce in southern California, with scant reports in San Diego County and the San Jacinto Mountains. I first saw one in the Santa Cruz Mountains in 2012, over a decade after I wrote Illustrated Guide to the Oaks, and my first in southern California within the San Jacinto Mountains a year later.

Golden Oaks

As for the golden oaks, the most widespread in San Diego County is canyon live oak (Quercus chrysolepis), a mountain species. On dry slopes it is a shrub but in deeper canyons and on mesic north-facing slopes it is a tree. The characters that set it aside are a deep green upper leaf with contrasting whitish to grayish underside; golden or silvery waxy hairs, at least on new growth foliage; and large, thick-cupped, warty acorn cups, the tubercles of which are embedded in short silky hairs. The scrub form has relatively small-toothed leaves while the trees have fairly large leaves with entire (smooth) margins. On the desert slopes, most easily found in the vicinity of Boulevard and the McCain Valley, is Palmer’s oak (Q. palmeri). This is an evergreen scrub oak with wavy, leathery or brittle leaves with teeth, each tooth tipped with a relatively sharp bristle. The acorns are moderate size and have an over-sized thin cup that appears almost as if it were a mushroom cap. I often tell students if in doubt, squeeze a leaf in your hand. If it is quite painful, you’ve got Palmer’s oak. Actually, I don’t recommend doing it though it does seem to work as an ID character.

Finally, there is Cedros Island oak (Q. cedrosensis). This is a bit of a non-descript oak in that it has a distinctive gestalt, but its characteristics are not so distinctive. The leaves are generally less than 25 mm (one inch) long. Like canyon live oak, it typically has green upper leaf surfaces, though these are somewhat yellowish gray green, and a whitish under side. The leaves can have teeth or not. The acorn doesn’t at all appear distinctive. The acorn matures in two years. One of its more distinctive characteristics is that it will grow roots at the branch nodes where it touches the ground. You don’t see this often in San Diego oaks though as many are erect. A classic Cedros Island oak, however, is a bit matted and on these you can find this node rooting characteristic. While undoubtedly Cedros Island oak has been here all along, it was only recently discovered in San Diego County. The first vouchered specimen was made on Otay Mountain in 1996. It is relatively common on the south side of the San Ysidro Mountains and Tecate Peak. Although reported at a couple sites farther north, I am suspicious of the identifications of these individuals. I examined one at the San Diego Natural History Museum a few years ago. I am certain it is a white oak. I am just not certain which white oak. While technically, these three golden oak species can hybridize, we haven’t seen clear evidence of it in San Diego County. Thus, the red oaks hybridize a bit, the golden oaks not much, but the white oaks are an entirely different matter. Before we get into the white oaks, the most abundant, diverse, and maddening group in San Diego County, it might be a good idea to step back and look at the history of oaks in San Diego County in next month’s newsletter.

~reprinted from the SD-CNPS newsletter with permission of the author